by Joe Monninger

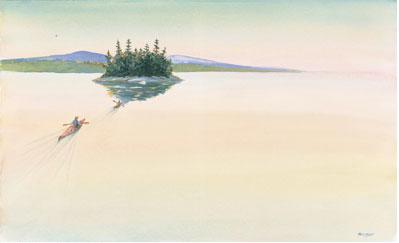

Illustration by Karel Hayes.

It was the last part of June, and hot, and my 11-year-old son, Pie, declared that he had never camped out. Oh, he had camped out, he said, when I raised my eyebrow. He had done the traditional backyard tent affair, complete with a work lamp connected to an inside socket strung all the way into the wild flower meadow behind our house. And he had car camped with another family, pulling up and emptying out a veritable household of goods at a nearby campground, but he had never, you know, camped.

“What do you mean?” I asked. “We went camping last year over at Basin Pond. In Evans Notch, remember?”

“But that wasn’t camping,” he said. “We could have gotten into a car and driven home. I want to go someplace and set up a camp all by ourselves. Someplace that isn’t easy.”

I checked the weather report. Clear and bright. Mars dangled at its brightest in the southeastern sky, the report said. The moon—the Strawberry Moon, some called it—glimmered like a yellow pig’s ear near the horizon. If we were going camping, what were we waiting for? A boy is only 11 once.

We spent a morning discussing possibilities, but settled on kayaking to an island in the middle of Lake Tarleton, just off New Hampshire’s Route 25C. We had talked for a long time about kayak camping, even debating how much stuff we could tether to the kayaks. Tents, sleeping bags, inflatable pads, water and food. I told Pie we didn’t need more than we wanted, and didn’t want more than we needed. While he chewed on that, we loaded the kayaks into the back of our old Dodge pick up.

Lake Tarleton is one of three relatively pristine lakes in Piermont, N.H., the other two being Lake Catherine and Lake Armington. Years ago a grand hotel stood on the brow of the height of land, but fire took the hotel and private interests ringed the water for decades. In a move that pleased many residents in the Warren, Piermont, Benton area, the state recently acquired an enormous tract of land near the lake and relegated it to public use. Now the state has delineated a small beach at the western end of Lake Tarleton, and the abutting forest stretches like a tablecloth for miles to the north and east. Fishing is excellent in all three lakes, but Tarleton is, by reputation, the best. A small island, nameless on the topographic maps, squats in the center of the western quadrant of Lake Tarleton. Pie Island, we called it. That was our destination.

At seven-thirty, we carried the kayaks down to the edge of the lake and discovered, to our dismay, that a family of geese had made a beach landing long before ours. Geese are marvelous things on an autumn night when they call, hurry, hurry, hurry, against a white moon, but on a beach they are poor company. The adult geese hissed and flapped their wings at our approach, reluctant to herd the goslings into the water. But at last they did and the five goslings, their question mark necks bowed forward, paddled off.

“Ick,” Pie said at the state of the beach.

“Nature at its finest,” I said. “Come on, we should get out to the island before sunset.”

Our Manatees, wide-beamed, beginner kayaks, provided limited storage behind the paddler’s seat. We stuffed our sleeping bags there. The sleeping pads we strapped to the bow of our kayaks with bungees. We shoved water bottles under our knees, loaded in a bag of Oreos next to the bottles, and finished by wedging flashlights anywhere that would hold them. Pie put on his lifejacket and spray skirt, then I pushed him off into the lake.

I followed. John Steinbeck, writing about that particular time of early evening when the sun is splintered by pine limbs and whatever wind existed a moment before finally ceases, called such sunsets “the hour of the pearl.” Whether an accurate description or not, it is true that the water this night calmed and flattened. The sun hung like a lollipop for a few moments on the topmost pines, then it fell and broke and became light diffused by mist. Pie, just ahead of me, turned and waited. I caught him in a few paddle strokes and for a while we didn’t do a thing except sit and listen. A perfect evening. Mosquitoes that followed us down from the truck to the beach retreated and sank away. Trout popped the water. They might have fallen from the sky so clearly did their rings hang for a second before disappearing.

“Ready?” Pie asked.

“Ready,” I said.

He was greedy for gear, for the camp set up. Mars, true to predictions, appeared in the time it took for us to paddle twice. Bright and red, it glowed like the end of an usher’s flashlight in a gloomy theater. Other stars began to follow, but this wasn’t the big show yet. That would come later, I knew, and so did Pie. I matched my stroke to his so that we would travel shoulder to shoulder. He paddled effortlessly and I marveled at how accomplished he was in a conveyance I had scarcely heard of at the same age.

The island—Pie Island—was an easy 10 minutes paddle. A few sharp rocks guarded the western edge, but Pie maneuvered his kayak through them with no difficulty. He hopped out of his kayak and pulled it up until its belly stood on the rocks. I copied his movements, then stood with him and looked around. I waited for the requisite loon calls, but they didn’t come. The sun fell behind the trees. Night started to pull the water up into the sky and tie it, by color, to the darkness.

Finally, Pie got to set up camp. He rolled out our sleeping pads while I retrieved the sleeping bags. We fluffed them around, made sure we could sleep right next to one another, then established a flat hunk of granite as our table. We put our flashlights there and our food. Pie pulled out the binoculars and examined the moon and Mars. By the time he finished, the loons had finally arrived. They called back and forth, that wobbling, distant trill that makes you want to live in the north woods forever. Pie scanned the water for sight of them, but they lingered out in the mist that began to rise from the lake surface.

Pie settled down into his sleeping bag and yanked out the Oreos. For a time we ate happily, listening to the loons and turning our heads to watch Mars. Then a satellite went overhead and Pie said he had never seen one. I told him a long story about going out on the back steps when I was about his age to watch Sputnik and Echo, but the story was too long and Pie listened mostly out of politeness. He wanted to talk about monsters, about what if someone, like 10 years before, had let a crocodile loose in Lake Tarleton. And what if, just pretend, that the crocodile had found a warm spring and had stayed next to it so that it didn’t freeze in winter. And what if the crocodile had now grown to about 20 feet and if it lived during the summer on this island. What would I do, he wanted to know, if the crocodile started to come up on the island right about now?

“I’d feed you to the crocodile and paddle away,” I said.

“You would not,” he said. “Besides, I could get in my boat much faster than you.”

“Did you hear something?” I asked.

“What?” he asked, suddenly serious.

“Like a slithery kind of noise?”

I had him for a fraction of a second before he grinned and dove on me. Then we settled back in our bags for good. Pie wanted to light our candle lantern. He did, but the moon threw enough light to do without it. Eventually he blew it out. Then the night gave us the good show. Stars stretched everywhere and we talked about what our first memories of the world were, why anacondas could probably beat up any snake in the world, whether King Kong or Godzilla would prevail in a death match. It depended, we decided, on whether Godzilla had radioactive breath as he does in some versions, or whether he simply had a vicious tail. King Kong could handle the tail, but not the radioactive breath. That was our assessment.

The loons continued to call and then an owl barked a little from the mainland. We heard coyotes a little later, then the oldest sound of all—mosquitoes grinding close to our ears in wild, hungry prospecting trips. Pie slid down into his bag to escape the mosquitoes, but not before imagining aloud that the island was really the back of a dinosaur and what if, during the night, the dinosaur decided to move? We’d be in a pickle I told him, and soon his breath became quiet and straight.

Summer and sleeping bags. I remembered sleep-outs of my own, nights when as boys we had crowded like so many seals around the linoleum floor of someone’s basement. And backyard camp-outs, orange tents and bug juice served warm as candle wax. This was better, but I liked remembering those old sleeping bag days. I watched the stars and thought about them until I fell asleep.

It was a long night for me, and not very comfortable, but when I woke the trout still popped the water and the island had not turned into a dinosaur. And Pie, when he finally hopped out of his sleeping bag, danced around in the summer cold. We made it, he said. Morning cracked over the lake and mist cut us off at the knees. We loaded the kayaks and paddled back. We were the only things moving for miles and miles.

Associate Professor Joe Monninger (English) has published eight novels and two non-fiction books, as well as articles in regional and national magazines and newspapers. He has won two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a Fulbright fellowship. This essay first appeared in the Valley News.