By Elizabeth W. Cheney ’89, ’99G

When Karl Drerup came to Plymouth Teachers College in 1946 as the sole art instructor, little did he imagine the art department as it would grow to be in 2007. When Drerup retired in 1968, the department he founded comprised 10 instructors and 133 students. Today, the department boasts a dozen faculty, plus numerous adjunct teachers, and upwards of 575 students learning about art and art education in any given semester, as well as a public gallery named for Drerup.

When Karl Drerup came to Plymouth Teachers College in 1946 as the sole art instructor, little did he imagine the art department as it would grow to be in 2007. When Drerup retired in 1968, the department he founded comprised 10 instructors and 133 students. Today, the department boasts a dozen faculty, plus numerous adjunct teachers, and upwards of 575 students learning about art and art education in any given semester, as well as a public gallery named for Drerup.

A highlight of the gallery exhibitions this year was the annual Faculty Exhibition, which ran from July 9 through October 13. The exhibition showcased the artistic endeavors of faculty and provided an opportunity for critical exchange. “The faculty exhibition celebrates and honors faculty as active artists and cultural agents, while inviting an ongoing dialogue with the artists, their works, and each viewer,” said Cynthia Vascak, art department chair.

The work of Terry Downs, senior art faculty member, illustrates this point. Downs says a sketchbook, rather than a camera, captures his experience of person, place, or thing as he travels throughout Europe, Central America, and New England. “[A camera] is lacking in its ability to provide the touch of the hand and eye,” he said. “This is drawing’s inherent ability.”

Downs collaborated with Rumney neighbor Edith Patridge, a Plymouth State alumna, poet, and teacher, to create The New Hampshire Village Suite of poetry and images, which was on display at the exhibition. The series pairs Patridge’s literary imagery with Downs’s visual expression. Compiling the suite encompassed seven years and yielded a body of 38 prints and poems—intimate reflections on the community in which they live.

“Rumney here is envisioned as a prototype for a rapidly transforming entity,” said Downs, “the quiet, rural, postcard-like New Hampshire village.”

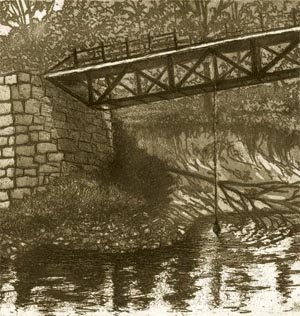

He and Patridge started by identifying a list, with help from family, friends, and neighbors, of not-to-be-missed landmarks in Rumney. A railroad trestle, a legendary swimming hole, the town common, the library and elementary school, alongside scenic vistas. Then, site-by-site, they went their own ways to consider and interpret the locations in their own media.

“Working together and thinking together is so transactional,” Patridge said. “Like living in this village—we don’t stand apart from the work, it informs us.”

Patridge’s poetry is expressed as a personal revelation, while Downs’s etchings employ a 19thcentury style of presentation, emphasizing the nostalgia of the circumstance. “The viewer is provided simultaneously with an appreciation for both the external reality and the inner experience associated with the site,” Downs said.

Patridge has described her experience of writing as reflective and heuristic, revealing personal insights on a given subject throughout the process of writing about it. “Writing helps me find out what I think about something,” she said. Downs has found his exploration provides a similar result, particularly so with The New Hampshire Village series. Both noted they “perceive our village anew.”

There is an intimacy in writing as there is in making art, so, while Patridge’s and Downs’s vocabularies differ, their shared sensibilities are apparent in the works; their reactions, insights, and interpretations often overlap. Both describe as “profound and profane” one particularly bucolic vista that is flanked by a house with an enormous satellite dish in the yard. The artists reacted with a sense of nostalgia and anxiety about the encroachment of modernity and the rapidly increasing loss of such vistas in the local area in Partridge’s poem “this” and Downs’ print “The End of Forever.” So too with their reflections on the iconic town common as the crossroads where neighbors meet, linger, celebrate, and congregate.

Over time, Patridge has developed a visual aspect for her poems through typography and layout as they conjoin with Downs’s drawings. “I wanted viewers to be struck by not only the content of the poem, but how it looked on the page,” she said. Visually, the poem about the railroad trestle (“Straight Track Compass”) resembles a railroad track; the poem about the Rumney Bog (“Saturday Naturalist”) suggests a scientist’s journal notes and was constructed without a beginning or end to represent the omnipresence of the bog.

Although The New Hampshire Village Suite had been exhibited widely throughout New Hampshire, the display this fall was its first on the PSU campus.

Downs received an MA from the University of Miami and an MFA from Florida State University before coming to Plymouth State, where he has taught printmaking and drawing since 1971. Patridge earned her BS and MEd degrees at Plymouth State and followed with postgraduate studies at UNH. She has published two books of poetry and was named New England Poet of the Year in 2000 by the New England Association of Teachers of English.

Straight Track Compass

With knowledge of schedules and steam warmed rail cars swaying on straight stretch of track to deliver milk mica from Groton mines students who would not did not ever miss the train stretched awake to frosty dawn breath-clouded vision as they walked half asleep to the station climbed aboard and were lulled back to sleep no more ever could we ask of you who did your lessons who climbed back on late that same day who did arrive in time who did not miss the train no one ever missed the up gone like an analogy useful in cases like a dis-connected train trestle which is what is left no more could ever we ask of you who have only partial knowledge of steam warmed cars schedules for no trains no tracks who walk over anything at all similar to a trestle useful like a compass.

With knowledge of schedules and steam warmed rail cars swaying on straight stretch of track to deliver milk mica from Groton mines students who would not did not ever miss the train stretched awake to frosty dawn breath-clouded vision as they walked half asleep to the station climbed aboard and were lulled back to sleep no more ever could we ask of you who did your lessons who climbed back on late that same day who did arrive in time who did not miss the train no one ever missed the up gone like an analogy useful in cases like a dis-connected train trestle which is what is left no more could ever we ask of you who have only partial knowledge of steam warmed cars schedules for no trains no tracks who walk over anything at all similar to a trestle useful like a compass.