by Barbra Alan

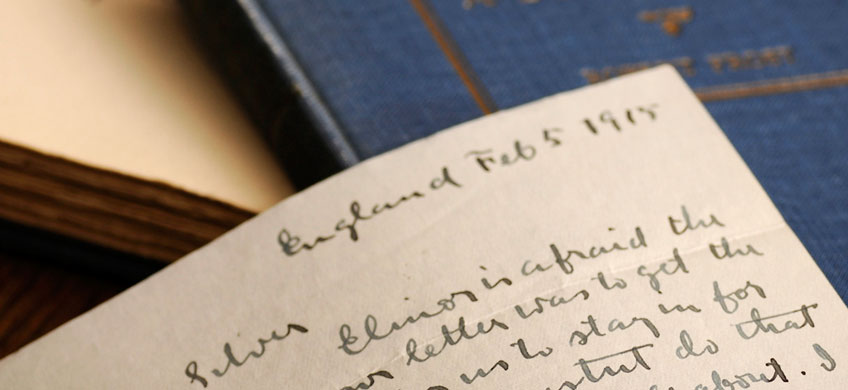

2011 marked the centennial of two momentous events in Plymouth State University’s history: the first year of Ernest Silver’s distinguished 35-year presidency of Plymouth Normal School, and the year poet Robert Frost taught at the school. Thanks to the support of generous donors, including Frost’s granddaughter Robin Hudnut, PSU celebrates both of these men with the acquisition of six letters written by Frost to his friend and former colleague Silver between 1913 and 1936. These letters join the books, letters, manuscripts, and other Frostiana that compose the George H. Browne Robert Frost Collection at the Michael J. Spinelli Jr. Center for University Archives and Special Collections.

Before Robert Frost was a beloved and respected poet, and before Ernest Silver was the iconic longtime president (or principal, as the position was known a century ago) of Plymouth Normal School, they were colleagues at Pinkerton Academy, an independent high school in Derry, NH. It was 1910, and 36-year-old Frost—married and a father of four—was balancing his life as farmer with his duties as English teacher at the academy, all the while developing his talent and voice as a poet. Meanwhile, 34-year-old Silver, an alumnus of Pinkerton who had distinguished himself early in his career as an exceptional school administrator, had been asked by his alma mater to reorganize its curriculum.

Theirs was an unlikely friendship: in their respective careers, Frost was known for his creative and informal teaching style, whereas Silver was known as a superb financial manager and a fair yet strict disciplinarian. But the two shared many common interests, including a love of athletics and a mutual respect for one another, and Silver was quick to recognize Frost’s emerging talent as a poet and to encourage Frost to nurture that talent.

Plymouth Normal School

In 1911, Silver was hired as principal of Plymouth Normal School and invited Frost to join him as a member of the faculty. While desperately wanting to devote himself full-time to his poetry, Frost realized he needed to make a living and accepted Silver’s invitation, with the proviso that he could resign after a year. With no openings in the English department, Frost taught education and psychology courses, and he and his family shared lodgings with Silver in what is now known as the Frost House.

“1911 was a pivotal year for Frost,” says Professor Donald Sheehy, a noted Frost scholar from Edinboro University in Pennsylvania. “In joining Silver at Plymouth Normal School, he was clearly moving up in the world of education … At the same time, he was deeply committed to his writing and was planning to use the proceeds from the sale of his farm in Derry to free him up to write full-time. So even as he was settling in at Plymouth, he had one foot out the door.”

Before Frost made the momentous decision to dedicate his life to his art, he made his mark at Plymouth Normal School. Stories abound about Frost’s unconventional ways. At the beginning of his first class at the normal school, for example, he called for student volunteers to help him clear off the stack of dog-eared copies of Monroe’s History of Education that were piled on his desk for distribution, and directed them to return the books to the stockroom. He then proceeded to acquaint his students with Rousseau’s Emile and Plato’s Republic. Another story has Frost, knowing that his friend and boss Silver is out of town, scrapping a lesson plan in favor of giving a spirited reading of Mark Twain’s “The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” to the amusement and delight of his class.

At the end of his year of teaching, Frost did indeed ask Silver to release him from his teaching duties so he could move to England and devote himself full-time to writing poetry and prose. Says Sheehy, “[Frost] was 38 years old; he had a wife and four children; he knew if he didn’t take this opportunity to devote himself to writing at that time, then he likely never would.”

Silver, ever the pragmatist, had reservations about his friend’s plan to leave the security of his job at the normal school, but ultimately supported Frost’s decision and helped get the family on a train to Boston, where they would begin their journey to England aboard the SS Parisian.

England

Frost and family would live in England from 1912 to 1915, during which time Frost devoted himself fully to his craft and lived very frugally so he could continue to do so.

The first letter in the Frost-Silver collection is dated May 7, 1913, less than a year after the family had arrived in England. In it Frost shares his excitement over the recent publication of his first book of poems, A Boy’s Will, and consequently finding himself moving in literary circles that included Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats. “One has only to write a little insignificant book like mine to be brought in contact with people who have done all sorts of things … I suppose I enjoyed most Yeats, the man who wrote the play I read to the 1913 girls in the parlor last winter.”

Also in the letter, Frost references his treasured “smoke talks” with Silver and proposes that they have a long-distance smoke talk on May 20 “in honor of the Normal School Class of 1913 at precisely seven o’clock p.m. Plymouth time ….”

In subsequent letters, Frost shares his misgivings about World War I and Kaiser Wilhelm:

“And I suspect the fear of what we would be in for if the Germans came makes us a little homesick for the furniture stored in your back attic”; his continued interest in Plymouth Normal School: “Did you get your gym?”; and his eagerness to see his friend Silver again: “I shall be glad if you will invite us to stay a few days in Plymouth. In fact I can see that I shant feel as if I had come home unless you do.”

The last of the letters in the collection, dated July 12, 1936, finds Frost and wife Elinor living in South Shaftsbury, VT. In the letter, he contemplates visiting the normal school and his friend Silver. Over the years, Frost did indeed visit the school frequently, giving readings and special presentations to students.

The letters in the Frost-Silver collection, Sheehy says, “offer further insight into a very crucial period in Frost’s development. The glimpses they provide of his mingling in British literary society are reason enough to be glad to have them, but … even more interesting [are] Frost’s remarks about his distaste for a class-bound society and its effects on children and education.”

For those who know and love Plymouth State, the letters offer even more: the knowledge that while its most famous faculty member was away from campus, publishing his poetry and growing into the legend we know him as today, Plymouth Normal School and his friend Ernest Silver were never far from his thoughts.

What archival treasures do you have?

Do you have any rare or historic items related to Plymouth State or the surrounding regions that you would like to share with the PSU community? Consider donating your treasures to the Michael J. Spinelli Jr. Center for University Archives and Special Collections, which collects, organizes, preserves, and makes accessible rare and historic items relating to the history of Plymouth State University, the North Country, and the Lakes Region of New Hampshire, in support of PSU’s mission to serve as a cultural resource for the region. For more information, contact Alice Staples, archives librarian, at astaples@plymouth.edu.

Top: Jon Gilbert Fox photo.