June 3, 2023 – September 16, 2023

Museum of the White Mountains, Main Gallery

Exhibition guest curated by Inez McDermott; Co-ordinated by Meghan C. Doherty; Graphic Design by Inna Horbovtsova, PSU Class of 2023

This exhibition explores the history of the Old Man of the Mountain and the ways in which its images and narratives symbolized and reflected the evolving identity of New Hampshire and its citizens. The extraordinary story of the people and technology involved in the innovative efforts to preserve the Old Man’s place atop Cannon Mountain will also be told.

Lenders for this exhibit include:

- Abbie Greenleaf Library, Franconia

- Adam Apt

- Ashland Elementary School

- Bryant F. Tolles, Jr.

- David and Deborah Nielsen

- The Honorable Elaine French

- Franconia Heritage Museum

- Gary Samson

- Gladys Brooks Memorial Library, Mount Washington Observatory

- Greg French

- Jayne and Bill O’Connor

- LaFayette Regional School

- Lawrence L. Lee Scouting Museum

- Littleton Area Historical Museum

- Karin Martel

- Manchester Historic Association

- Michael J. Spinelli, Jr. Center for University Archives and Special Collections, Plymouth State University

- Michael Mooney and Robert Cram

- Milne Special Collections & Archives Division, University of New Hampshire

- Molly Dorman and Steve Weisman

- New Hampshire Historical Society

- NHIOP Political Library, Saint Anselm College

- P. Andrews and Linda McLane

- Salem Historical Museum

- Sandy and Trevor Hamilton

- Wayne Haubner

- White Mountain Railroad at Clark’s Trading Post

For more information on specific topics relating to the Old Man of the Mountain and Franconia Notch, please visit our summer event series page.

An Enduring Presence

Twenty years ago, the Old Man of the Mountain fell from its perch high above Franconia Notch. Many admirers in New Hampshire and beyond mourned the loss. For more than 200 years the jagged ledges that formed a human profile promoted New Hampshire’s identity, inspired works of art and literature, and symbolized the beauty and fragile environment of the White Mountains.

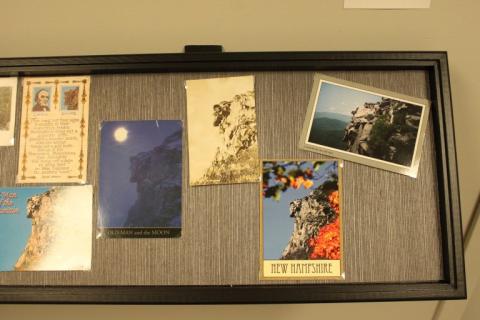

The Old Man of the Mountain helped make the White Mountains one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Northeast. Nineteenth-century writers imbued the Profile with qualities often used to describe beloved leaders, ancient philosophers, or even gods. Then and now, the image has appeared in art, advertising, signs, and products. Its use ensured recognition far beyond first-hand viewing experience.

The fragility of the Profile had been well-documented since the mid-nineteenth century. From 1916, individuals and work crews made repairs to protect and preserve the Old Man. In turn, the Old Man played a central role in protecting and preserving Franconia Notch. It was a symbol and focus for establishing a state forest, memorial park, and environmental legislation.

Despite its absence, the Old Man continues to play an outsized role in the lives of so many people in the state and around the world. In tangible and intangible ways, the Old Man remains an enduring presence in New Hampshire.

A Draw for Creators

Nineteenth century artists and writers were drawn to the White Mountains for its picturesque beauty and rugged terrain. Cataclysmic natural events and awe-inspiring views attracted people interested in experiencing and depicting the beautiful and the sublime aspects of the region, and exploring deeper meanings that might be found in nature.

In the first decades following its documented discovery, the Old Man was not remarked upon with any great enthusiasm. Thomas Cole, often called the father of American landscape painting, visited the Notch in 1828 and sketched the Profile in his notebook. He commented that the “bold and horrid features” were “too dreadful to look upon in my loneliness.” He expressed his discomfort with the entire scene, “The stillness of this lake and the silence that reigned in this solitude was impressive . . . the sublime features of nature are too severe for a lone man to look upon and be happy.” British writer Harriet Martineau was not moved. She responded indifferently in 1838. “The sharp rock certainly resembles a human face – but what then?”

By mid-century, however, many more appealing characteristics were attributed to the Profile. Several writers, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, depicted the Old Man as a benevolent overseer: ancient, stoic, and wise. Tales of the Old Man’s role in Indigenous cultures were widely published. Dozens of poems and odes paid homage to the Profile.

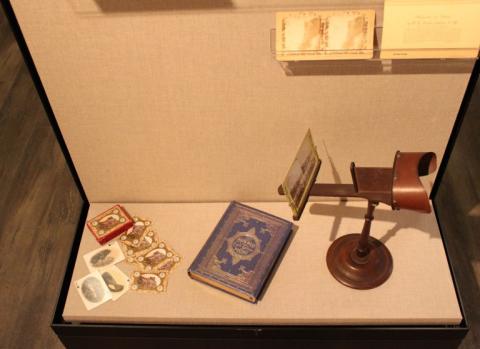

Samuel A. Bemis, a Boston dentist, was likely the first landscape photographer in New Hampshire. The earliest photographic process, the daguerreotype, was introduced in Boston in 1840, and Bemis brought his newly purchased camera and kit with him to his summer residence in what is now Crawford Notch. For that summer, and the next few years, he documented the White Mountain landscape. On September 9 and 10, 1841, he made eight exposures of the Old Man. This image of the Profile is the only one extant, and if you look closely at the top right, you can see faint evidence of the windows of a building. This is likely the nearby Lafayette House traces of which were left when Bemis wiped the plate clean before reprocessing it for his new photograph. According to Bemis’ records, this exposure (meaning the amount of time that the treated plate was exposed to light through the camera lens) took one hour and thirty-six minutes. Daguerreotypes a one-of-a-kind image on a silver-coated copper plate, which results in a mirror image.

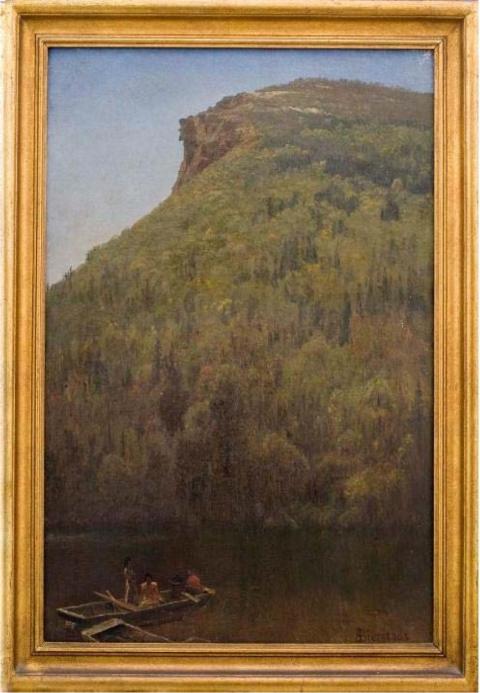

Thomas Doughty is considered one of the founders of American landscape painting. Largely self-taught, the artist developed an interest and proficiency in landscape painting by copying European paintings available to him through the collections of wealthy patrons and then applying his careful observations of the natural world. In 1828, when the artist traveled to Franconia Notch from Boston on a sketching trip, the Profile was merely a curiosity, and would likely not have had the same appeal as this romantic view of Echo Lake.

Becoming a Destination

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the White Mountains became one of America’s first tourist destinations. The rugged beauty of the White Mountains embodied an emerging national pride in the American landscape. In the 1850s, the introduction of rail travel provided easy access from Boston and New York City, and visits to the White Mountains increased. Travelers were armed with guidebooks that told them where to go, what to think, and how to feel.

The Old Man was a must-see tourist attraction, with most guidebooks providing suggestions for best viewing times and locations. Since most tourists stayed for multiple weeks, they had many opportunities to experience a clear, if not inspiring, view.

In Franconia Notch, inns and hotels were built to accommodate the large numbers of visitors arriving to see the Old Man, the Flume, and the Basin. Early hotels in the region, the Flume House and the Lafayette House, were precursors to the grand hotels. The largest of these, the Profile House, opened in 1853 and occupied the land between Echo and Profile Lakes. In 1923, when the hotel closed, it could comfortably entertain 600 guests.

Edwin Burgum, like his father John, was an ornamental painter for the Abbot-Downing Company in Concord, New Hampshire. Concord coaches were distributed world-wide and were renowned for their innovative suspension systems that made for a smoother ride over rough roads. The Concord Coach that featured this door was likely used to deliver mail and passengers along various routes in the White Mountains

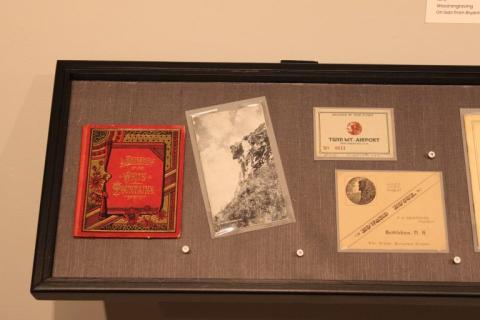

Profile Railway Ticket Punch, after 1879. On loan from White Mountain Central Railroad at Clark’s Trading Post.

In the 1840s travelers to the White Mountains would travel by train from Boston to Concord, and then transfer to points north via stagecoach. By 1853, there were regular trains to Laconia, Plymouth, and Woodsville, with additional routes added to Littleton and Gorham by the end of the decade. The Pemigewasset House in Plymouth served as the point from which those traveling north would transfer to rail or stage. Well into the 1870s, a traveler headed to Franconia Notch by train would disembark at Plymouth, enjoy a meal, and continue by rail to Littleton or Bethlehem. A stagecoach would deliver guests, sometimes along with the mail, to the Profile House and other local inns. In 1879 a narrow-gauge rail line from Bethlehem was constructed directly to the increasingly popular Profile House. Passenger tickets were validated with a special “Old Man” punch. The Profile and Franconia Notch Railroad was shut down in 1921, as by then most guests arrived by automobile. The “Old Man” punch continued to be used, however, on the White Mountain Central Railroad at Clark’s Trading Post in Lincoln.

The first dedicated tourist accommodations in Franconia Notch and throughout the White Mountains were essentially farmhouses with rooms and a tavern. One of these early lodging houses, the Lafayette House, opened in Franconia Notch in 1835. Owner Richard Taft and his partners eventually incorporated the Lafayette House into a larger new hotel, the Profile House, in 1852. When Charles Greenleaf partnered with Taft in 1866, additional improvements were made. Expansions and rebuilding continued throughout the next decades to accommodate increasing numbers of visitors and their evolving needs.

After being rebuilt during the winter of 1906, the “New Profile House” expanded to include 20 seasonal cottages for rent, and later purchase, for returning residents. Twice a day wagons would take guests through the Notch to visit the Old Man, the Flume, the Basin and other sites, and return to the hotel for tennis, bowling, boating, swimming, hiking, trail riding, golf, and many other activities. Evenings brought musical and dramatic performances. The extensive menu featured delicacies from afar, as well as food from on-site and local farms. The wine list was considered among the best in the region.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, British transferware—mass produced ceramics that featured images transferred from etchings and engravings—grew in popularity. They became popular tourist objects well into the early 20th century. Most plates and other items with the Old Man’s image were produced in this manner.

Special designs were created for the Profile House dinner service ware. This example was created for the “New” Profile House, which was rebuilt in 1906.

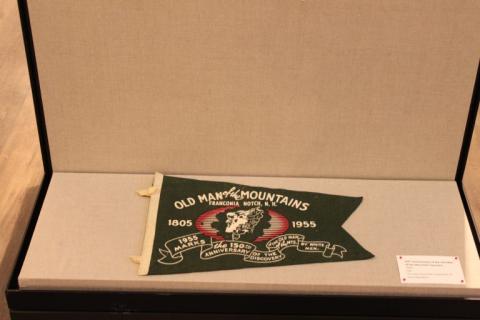

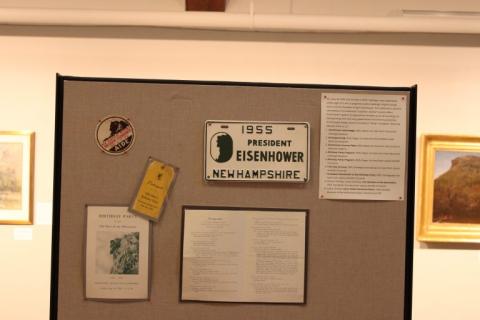

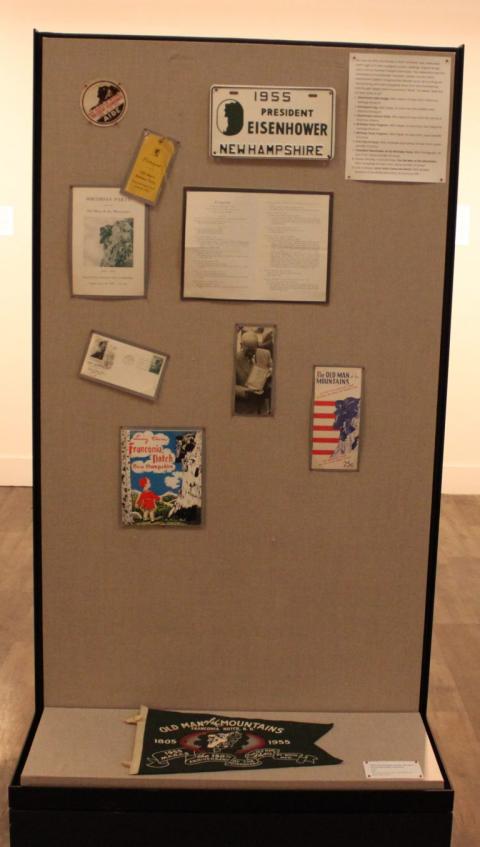

On June 24, 1955, the Old Man’s 150th “birthday” was celebrated within sight of it with a pageant, poetry readings, original songs, and a visit by President Dwight Eisenhower. The celebration was the centerpiece of a statewide “Vacation Jubilee” tourism effort. Eisenhower’s speech imagined the Old Man as an all-knowing, all-seeing being, who had long gazed down from the mountaintop and thought deeply about humankind. “What,” he asked, “does the Old Man think of us?”

Edward Hill settled in Lancaster, New Hampshire in 1874, and later moved to Littleton, where he became friendly with photographer and stereograph manufacturer, Benjamin West Kilburn. Hill was an artist-in-residence at the Profile House from 1877-1892. His range of subjects included not only the Old Man, but other popular local sites, including the Flume and the Basin. Like many artists-in-residence who spent the tourist season at one hotel, Hill would sometimes visit other inns and hotels after the busy summer months. The drawing on the Flume House menu may have been made during one of these periods. The Flume House was five miles south of the Profile House.

A prolific artist, Samuel Gerry spent nearly every summer in the White Mountains from the mid-1830s until 1890, sketching and painting, then exhibiting his works during the winter in Boston and New York. The Old Man of the Mountain and other scenes in Franconia Notch were among his favorite and most popular subjects. During his later years he began to produce works in watercolor. The medium was becoming popular with artists and audiences by the end of the nineteenth century.

Although Albert Bierstadt may be best known for his enormous paintings of the American West, he spent a good deal of time in the White Mountains, first visiting in 1852 and again in 1858, when he made sketches for his paintings of the region. In the summers of 1860 and 1861 he returned with his brothers as they made photographs for their stereograph book, Gems of American Scenery.

Stony Observations

From the late eighteenth century, the high altitudes and rocky peaks of the White Mountains attracted amateur and professional scientists to the region’s botany, minerology, meteorology, and geology.

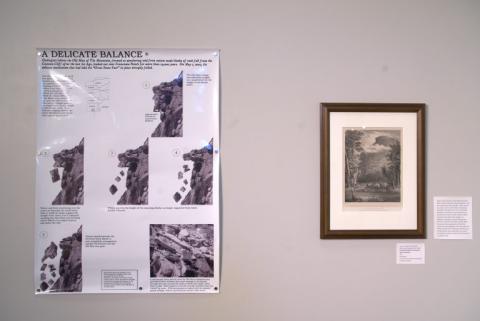

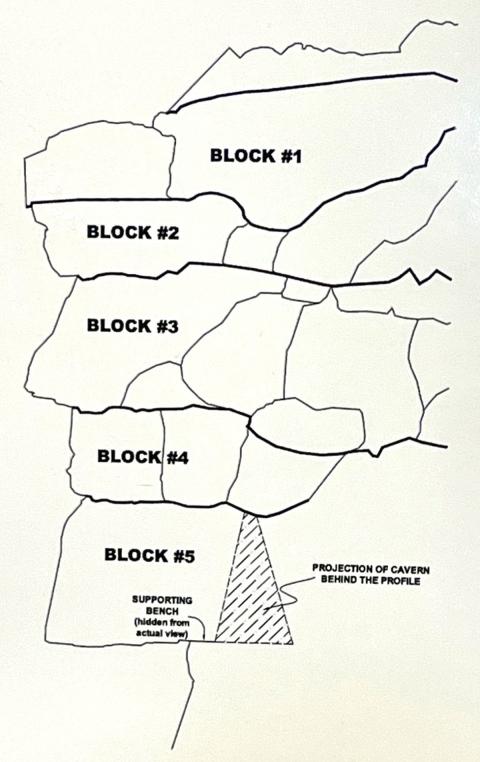

The Profile drew geologists who researched the meteorologic and geologic events and glacial movement that formed its five ledges. They examined the unique qualities of Conway granite, the specific stone type forming the Profile. Scientists also studied the effect of changing weather patterns on the fragile site.

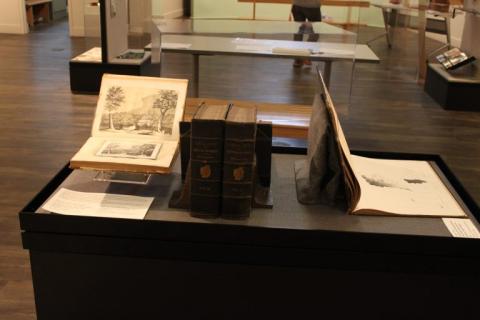

Comprehensive geological reports that paid particular attention to the Old Man were submitted by state geologists in 1844 and 1878. They included sketches and renderings alongside facts and figures. Geologist Charles Henry Hitchcock was well aware of the instability of the structure in his report in 1878. He warned readers, “I would advise any persons who are anxious to see the Profile…to hasten to the spot.”

In the mid-twentieth century, seismologists and engineers conducted numerous studies to determine whether proposed construction of the interstate would further destabilize the Old Man. Geologists continue to research the glaciation of the area of the Profile, and since 2003 have examined the series of events that led to its fall.

When Europeans settled in the Northeast and eventually reached the White Mountains, they found well-established trails used by Indigenous peoples throughout the region. Trails through Franconia Notch were close to areas from which the Profile would have been seen and tales of how the Old Man came to be perched above the Notch are part of Indigenous oral culture.

The first documented references to the Old Man of the Mountain by white settlers are two remarkably similar stories attributed to members of surveying parties. In both cases the rocky silhouette was first seen in 1805 on an early August morning at the base of Ferrin’s Pond (now called Profile Lake). The workers quickly alerted their companions, one insisting that the profile was that of then President Thomas Jefferson.

By the 1820s, atlases and scientific journals were calling attention to the Profile. In 1823, Farmer and Moore’s A Gazetteer of the State of New-Hampshire described the “singular curiosity…which exhibits the profile of the human face, of which every feature is conspicuous.” It was not until the mid-nineteenth century, however, that the Old Man of the Mountain became a destination for all those who journeyed to the White Mountains.

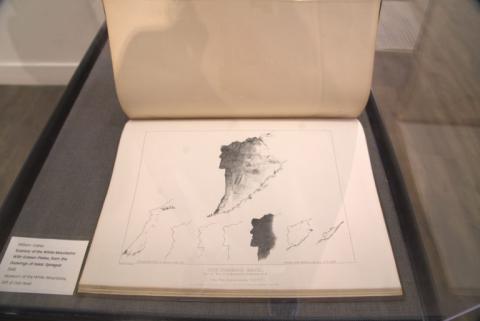

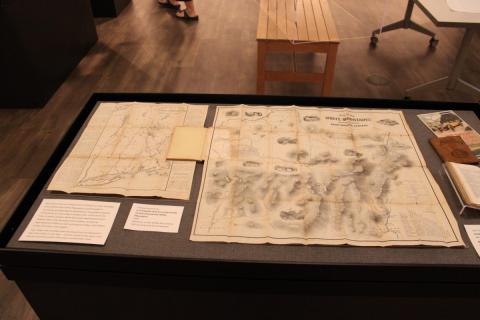

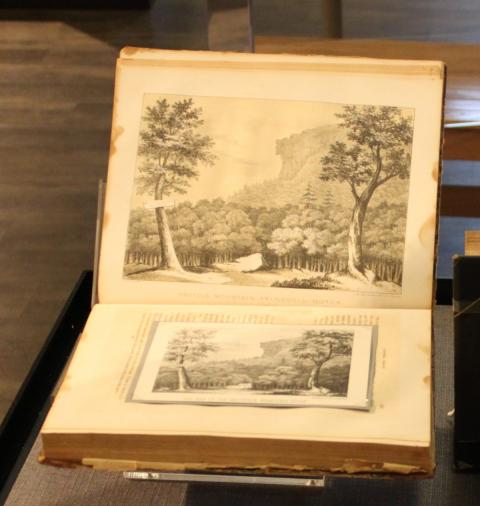

William Oakes’ Scenery of the White Mountains, 1848, contains sixteen full-page lithographs, most from drawings by Isaac Sprague. Oakes, trained as a lawyer, was a noted botany and geology enthusiast, who spent much time in the White Mountains. In the 1840s he was determined to document the most accurate scenes of White Mountains and asked Isaac Sprague, an assistant to Audubon, to make the drawings. Those he made of the Old Man carefully detail the viewer’s visual experience as the Profile comes into view. Sprague’s work was praised by Charles Hitchcock in his Geology, asserting that the illustrations were made with an accuracy and attention worthy of mention and inclusion in a scientific study.

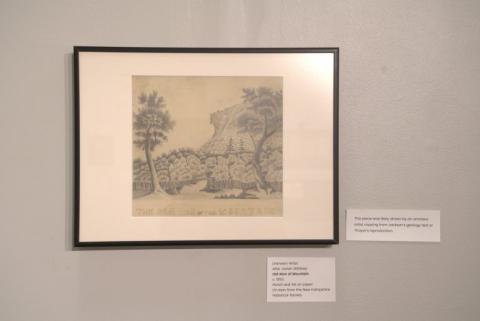

Charles Henry Hitchcock’s 1878 survey included artists’ renderings and photographs. Among them was the first published reproduction of a sketch of the Old Man by “a gentleman from Boston,” which had originally accompanied a description by General Martin Field and was first published by noted scientist Benjamin Silliman in the American Journal of Science and the Arts in July 1828.

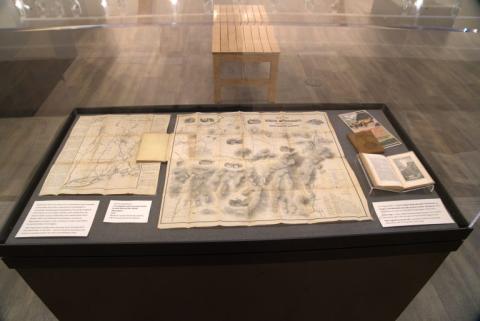

Boardman was a surveyor from Connecticut who traveled to the White Mountains frequently to participate in surveying and geological expeditions. His guide is typical of the time, as it provides travelers with instructions for how to reach various White Mountain destinations from Boston, New York, Montreal and Quebec, as well as descriptions of sites to visit, activities to enjoy, and where to eat and stay in the region.

Two maps are included with the book that correspond to the information in the text – one for travel to the area, and one for traveling within the area and between sites.

Josiah Dwight Whitney was a recent Yale graduate when he joined Charles Jackson’s geologic survey team in 1840 and was tasked with providing sketches for Jackson’s 1844 report to the state. Whitney’s rendering of the Profile was widely reproduced and copied both for publication purposes and by amateurs.

Benjamin Thayer copied Whitney’s illustration as seen in Jackson’s Geology. It was not unusual for print publishers to reproduce images from other artists and publications.

The Face of New Hampshire

Men hang out their signs indicative of their respective trades;

shoemakers hang out a gigantic shoe; jewelers a monster watch;

and a dentist hangs out a gold tooth;

but up in the Mountains of New Hampshire,

God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there He makes men.

Attributed to Daniel Webster

For many people in New Hampshire and beyond, the Old Man represents meanings and values that are associated with the state’s history and identity. When author and orator Thomas Starr King called the Profile a “most attractive advertisement” in 1859, he referred to its ability to interest travelers in the wonders of Franconia Notch and the White Mountains in general. The epigram attributed to Daniel Webster expands upon Starr King’s assessment of the Old Man, implying that the presence of the Profile signifies that the best of humanity was made in New Hampshire. This high-minded association has likely contributed to the icon becoming a symbol of pride and identity for New Hampshire’s history, culture, and values.

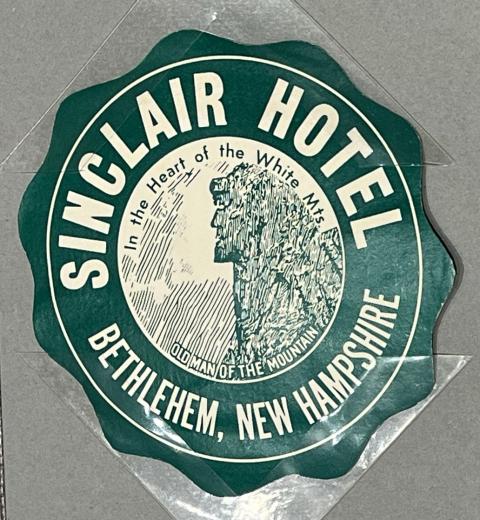

Despite its twenty-year absence from the cliff, politicians and protestors continue to incorporate the Old Man’s image in their messaging, as do the New Hampshire Boy Scouts and several state and municipal agencies. The state emblem, introduced in 1945, features the Profile encircled by the state motto “Live Free or Die.” The Old Man is prominently featured on New Hampshire license plates, licenses, state trooper vehicles, and road signs. Chambers of commerce, small businesses, beer and liquor brands, clothing stores, and tourist stops still use the image in their advertising as an easily recognizable symbol of the state.

The Old Man continues to be featured in political campaign materials, protest signs, and other forms of political messaging. Both Republicans and Democrats have incorporated the image of the Old Man as a reference to New Hampshire identity and to signal a proud sense of independence. Republican Governor Chris Sununu has featured the Profile in his campaign materials since 2010. A spokesperson stated that its presence “serves to honor the spirit and independence of the people of New Hampshire.” Democrat Wayne Haubner, a former State Senate candidate, included the Old Man’s profile on a “Protect Trans Youth” sign at a rally in March 2023, explaining, “The powerful symbol of the Old Man of the Mountain signifies the unique spirit that has always been part of New Hampshire.”

The Old Man’s presence in New Hampshire will endure. On the twentieth anniversary of its fall, with bipartisan support from the New Hampshire legislature, the Governor signed a bill establishing May 3 as Old Man of the Mountain Day.

Granite State Potato Chip Company, founded in 1907 in Salem, New Hampshire, was one of the first potato chip companies in the world. They long maintained another first – the first company to use the Old Man in their advertising and logo. However, decades before, the New Hampshire Fire Insurance Company, founded in Manchester in 1869, began depicting the Old Man in its advertising and as part of their company identity. In subsequent years, many commercial brands and services featured the Old Man in their advertising and even today, twenty years after the fall, we continue to find the Profile used as a marketing or brand symbol.

Threats and Compromises

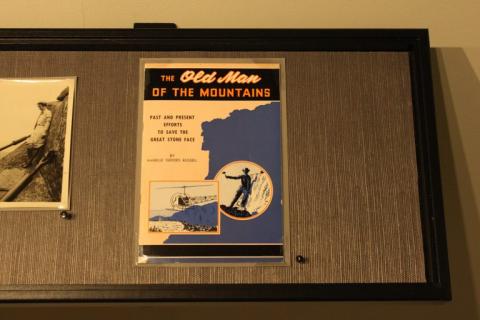

When the Profile House was destroyed by fire in 1923, owners Frank and Karl Abbott contemplated selling the timber rights of their 6,000-acre property to logging companies. This caused enormous public concern. For decades, the harmful effects of logging in the White Mountains had plagued New Hampshire residents and tourists.

To save the Notch, the state pledged half of the $400,000 purchase amount with the remainder raised by The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (SPNHF) and the New Hampshire Federation of Women’s Clubs. The Old Man was an important symbol of these efforts. Saving the Notch meant saving the Old Man.

The Franconia Notch State Forest and War Memorial was dedicated on September 15, 1928, to “the men and women of New Hampshire who served the nation in time of war.”

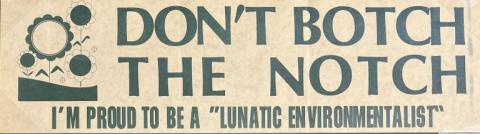

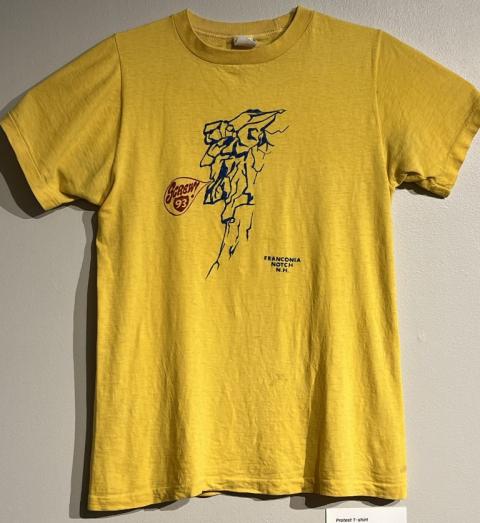

Four decades later, the Old Man was once again at the center of efforts to save Franconia Notch. Plans to connect northern and southern stretches of Interstate 93 through Franconia Notch were challenged by the SPNHF, the Appalachian Mountain Club, other concerned organizations and private citizens with fears expressed that both the construction of the highway as well as increased traffic would threaten the fragile rock formation. Protests and legal challenges continued for more than a decade. A compromise resulted in a two-lane parkway with lower speed limits, constructed with a minimal amount of blasting and less intrusion on the landscape. The Franconia Notch Parkway opened in 1988.

Frances Ann Johnson Hancock of Whitefield, New Hampshire, was an educator, historian, playwright, poet, and composer, who focused on the history of New Hampshire, and especially that of the North country and the Old Man of the Mountain in her creative, educational, and journalistic pursuits. Her song Old Man of the Mountains was sung both at the 1928 dedication of the Franconia Notch Reservation and War Memorial and at the 1955 Birthday Party celebration. In later years, her chronicle, Saving the Great Stone Face, provided a well-researched, first-person account of efforts to save the Notch.

By the mid-1960s, large stretches of Interstate 93 had been constructed north and south of Franconia Notch. The Old Man of the Mountain was at the core of public concerns as plans to connect the highway through the Notch were debated. Many feared that vibrations created by construction would endanger the Old Man, that the natural and rugged beauty of the area would be destroyed, and that traffic traveling at high speeds would further endanger the Profile as well as compromise the natural landscape throughout the Notch.

The debate continued for over a decade, with public protests and legislative and legal challenges. In 1974, Judge Hugh Bownes of the Federal District Court of New Hampshire opined, “It would be a crime to take even a slight risk of depriving future generations of the view of this legendary granite face so as to satisfy our present demand for speedy uninterrupted automobile travel.”

In 1976, a compromise was reached, and the Franconia Notch Parkway opened in 1988. The two-lane parkway was constructed with less intrusion on the landscape and with a minimal amount of blasting. Its lower speed limits allowed for a more leisurely trip and provided many with a lasting memory of their first glimpse of the Old Man as they traveled through the Notch.

Suspending Fate

By the late nineteenth century, it was apparent that the five ledges forming the Old Man of the Mountain were in a precarious state. Many hikers had called attention to the forehead ledge, which seemed to be sliding forward. A White Mountain Echo writer feared, in 1878, that one of the “glories of Franconia Notch… will have to be counted among the ‘has-beens’ of the grand old Granite Hills of New Hampshire.”

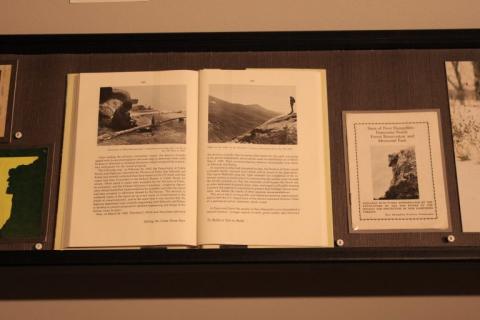

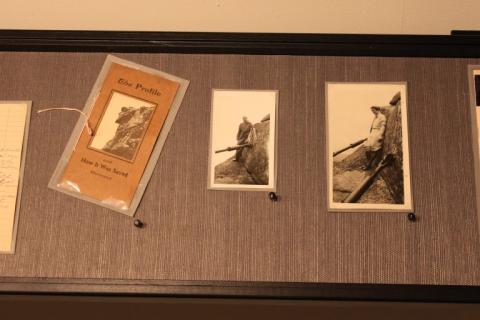

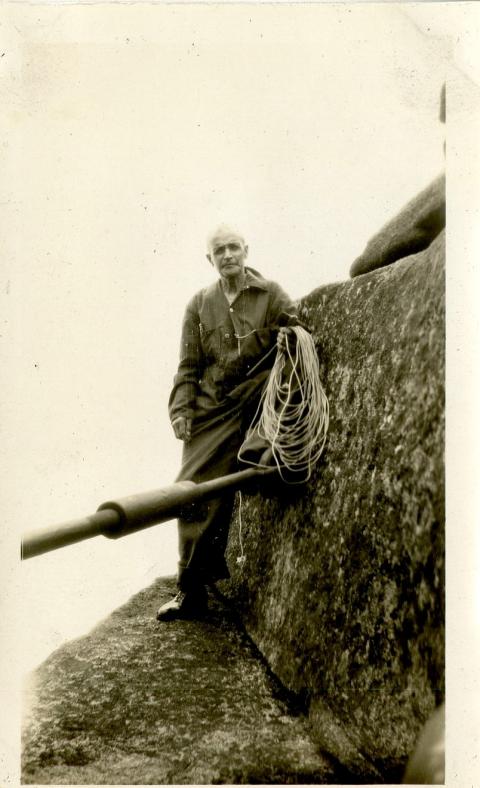

A fall seemed imminent, yet, with some assistance, the Old Man would continue to cling to its perch for over a century. In 1916, Edward Geddes, a quarry supervisor from Massachusetts, spent eight days installing a system to slow the deterioration. The quarryman designed a series of turnbuckles to prevent the ledges from shifting too far while allowing for seasonal expansion and contraction. The State of New Hampshire funded the project, despite it being private land, recognizing that the Profile was of great value to the state. In 1937, Geddes returned, made some additional repairs, and confirmed that there had been no further movement of the ledges.

In the following decades, volunteers and state workers continued to ensure that the Old Man was stable. The state funded annual inspections and repairs from 1958 until the summer of 2002.

Edward Geddes inspected the Profile for the last time in 1937 and determined that there had been no movement of the forehead ledge since 1916. He installed concrete blocks along the crack for future inspectors to measure changes. Sporadic inspections continued and in 1954 it was discovered that the crack had widened by ¾ of an inch. Returning in 1958 crews installed four large turnbuckles and placed a waterproof cover over the crack. State Highway crews returned each year to inspect and make necessary repairs.

In 1960, Niels Nielsen, a bridge supervisor for the state highway department was asked to join the inspection team. Five years later he was put in charge of the annual checkup and repair. In 1972 the crew installed a membrane of wire cloth sealed a crack on the south face and a fiberglass covering was fashioned for the ear. Various tags and measuring devices across the face were also installed in those years to check movements more accurately.

Niels Nielsen was given the official title of The Old Man’s caretaker by Governor John Sununu in 1987. While state workers played an important role in the repairs, the press corps tended to focus on the gregarious Nielsen. Long after his retirement from preserving the Profile, he continued to lecture about the efforts to save the Old Man. Niels Nielsen died in 2001, and his son David, who had worked alongside his father for many years, was later named official caretaker by Governor Judd Gregg.

A Last Glimpse

Dick Hamilton, President of White Mountain Attractions, dedicated his life to the White Mountains and mentored many people and organizations who shared his love for the region. Every evening as he drove home north through the Notch he would glance over his shoulder. “Goodnight, Boss” he would say. On Friday, May 2, 2003, his last good night was uttered, prophetically, the Profile obscured by clouds, “Goodnight, Boss, wherever you are.”

On the morning of May 3, 2003, a Franconia Notch State Park trails crew discovered that the Old Man of the Mountain was gone. Within hours many people whose lives and livelihoods were entwined with the Profile gathered in shock, sadness, and confusion. Governor Craig Benson convened a task force to explore options for “revitalization” of the Profile. Many ideas, reminiscences, and opinions were shared with the committee via public meetings, emails, and websites.

After months of deliberation, the Old Man of the Mountain Revitalization Task Force announced that no replica of the Old Man would be constructed at its original location. Instead, they proposed plans to develop appropriate tributes at the base of Cannon Mountain stating, “Man was able to help preserve nature’s work for a short time. But this symbol of New Hampshire’s natural beauty and of its people’s independent spirit will endure if we choose. . . We recommend against the creation of an artificial object on the site itself.” Today, Profile Plaza honors many who played a significant role in promoting and maintaining the Profile throughout the past two centuries. In addition, special “profilers” allow visitors to recreate the thrilling view of the Old Man as they look up from the base of Profile Lake.

On May 16, 2023, with temperatures hovering around 40 degrees and some snow and wind, photographer Gary Samson recreated Samuel Bemis’ daguerreotype using the collodion wet-plate process, an alternative process from the same era. He located a point close to where Bemis set up his tripod and made an exposure with an historically accurate whole plate view camera, albeit with a faster lens that decreased the exposure time to only twenty seconds. The collodion process was invented in 1851 and replaced the daguerreotype as a less expensive and more versatile method of making positive images through tintypes, ambrotypes, or with glass negatives which could then produce multiple positive prints.

Samson was assisted by photographers Claudia Rippee and Bev Conway, as well as Museum of the White Mountains Director, Meghan Doherty, and Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund President, Brian Fowler.

Jocelyn Paradis (PSU’24) documented the process.

To view the work of Matthew Maclay please visit “The Old Man of the Mountain in 3D.”