Launching October 14

Online/ Museum of the White Mountains, Main Gallery

Co-curator: Kimberly Ritchie

This exhibition features environmental artwork from Kimberly Ritchie’s recent sabbatical experiences in Greece and Iceland. The exhibit also highlights faculty led, student made, collaborative work from interdisciplinary projects across campus, involving the intersection of the human race and the natural world that impacts endangered, invasive, undiscovered, and evolving species.

Science inspires Art. The natural world and its systems have motivated Artist and PSU Professor Kimberly Ritchie’s art practice, leading her to explore at-risk environments, and to experiment with communicating ecologies via a mixture of media including printmaking, photography, and sculptural objects. Her passion for bridging disciplines in her work infuses her teaching through cluster connected class projects

Endangered Species

Over the past few years I have been working collaboratively with my classes, combining environmental research with art based concepts to create cluster project-based work. For two years I worked with my Plymouth State University First Year Seminar/Tackling a Wicked Problem courses, Art and the Natural Environment, in creating two separate endangered species exhibitions.

The first year focused on global endangered animal species that developed into a multi-faceted cluster project and exhibition, Vanishing Act, in the Silver Center for the Arts.

The second year, the class focused on a regional environmental topic, endangered New England plant species. This developed into an exhibition, Uprooted, at PSU’s Lamson Library as well as selected artworks in this exhibition.

The second year, the class focused on a regional environmental topic, endangered New England plant species. This developed into an exhibition, Uprooted, at PSU’s Lamson Library as well as selected artworks in this exhibition.

UPROOTED:Endangered Plant Species

On view in Lamson Library

October 15 – December 10, 2018

How can art bring awareness and change to environmental issues?

PSU’s First Year Seminar: Art and the Natural Environment students, a course designed by Kimberly Ritchie, explore the power of art to inspire activism. Students researched various endangered plant species in New England and created an accompanying art installation. Keeping in mind that the exhibit as well as the artworks can bridge understanding and raise awareness, students worked with Museum of the White Mountains staff to design, plan, and install Uprooted. This was the second year that Ritchie’s course focused on endangered species, this time bringing the focus closer to home for the students in New England.

In both exhibitions, students created wall art murals using hand cut vinyl decals. Students presented their artwork paired with their scientific research on endangered New England plant species and global endangered animals. The student research resulted in a common conclusion that the species were becoming endangered due to human impact on the landscape through deforestation, farming, and residential and commercial development, which has devastated habitats. Students discovered that the most important components to reflecting on species loss is to educate others, bring awareness, and create action.

For these projects, vinyl backings from earlier Vanishing Act and Uprooted exhibitions (which were destined for the trash) were used the cut-outs as a layer in multiple layered silkscreen and cyanotype plant prints. These works are a true collaboration with my classes in every way. My environmental art practice and my teaching practice are deeply connected. I continue to be inspired by my students and am always looking for ways to collaborate with them.

Invasive Species

During my Spring 2019 sabbatical, I had the opportunity to participate in The Skopelos Foundation for the Arts’ Artist Residency on Skopelos Island in Greece. During my stay, I would walk down to the small rocky town beach on the Aegean Sea every day. Instead of searching for shells and sea glass, I collected remnants of sea weathered fragments of man-made objects like sea glass, sea plastic, wire, and rope. I began reflecting on the dichotomy of humankind’s long history of collecting sea glass as compared to finding and thinking about these modern day sea plastic fragments as treasured objects. After collecting these fragments, I would return to the studio and arrange them in various compositions on treated cyanotype paper, and develop the image through UV sun exposure. I tinted the shapes to represent the realistic salt and sun washed colors of the found fragments.

The work shown here represents these “specimens” gathered from my experience of the Aegean Sea. But similar juxtapositions of sea glass and sea plastic specimens can be found throughout the world, amounting to an alarming reality of our modern day oceans. This realization has resonated with me as being connected to my plant series work. It seems that we, humans, are the invasive species. Action is needed. Nature is deteriorating under the impact of modern society. We must push to protect nature and take responsible ownership of our actions in order to change course.

Undiscovered Species

In my own work, I wanted to focus on Undiscovered Species as part of this exhibition in order to highlight the unknown elements of how earth systems work, to explore what we don’t know or understand, and to emphasize that there are still species that have yet to be discovered.

The “undiscovered” allowed me, as an artist, the freedom to simply create, letting go of reality’s constraints and inventing “species” that might be discovered.

As part of this exploration, I worked collaboratively with Denver-based artist Fawn Atencio to design plant inspired printmaking installations, sculptures, and concept prints/drawings. Modeling Nature as the essential creative and responsive force, has led me to be both more grounded in the workings within plant species’ ecosystems, and more open and aware of what might be evolving. Nature has it figured out, we humans do not. We have a lot more to learn from it.

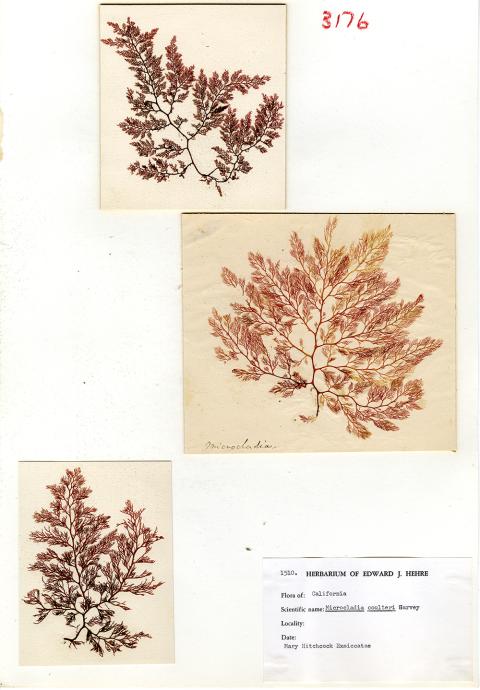

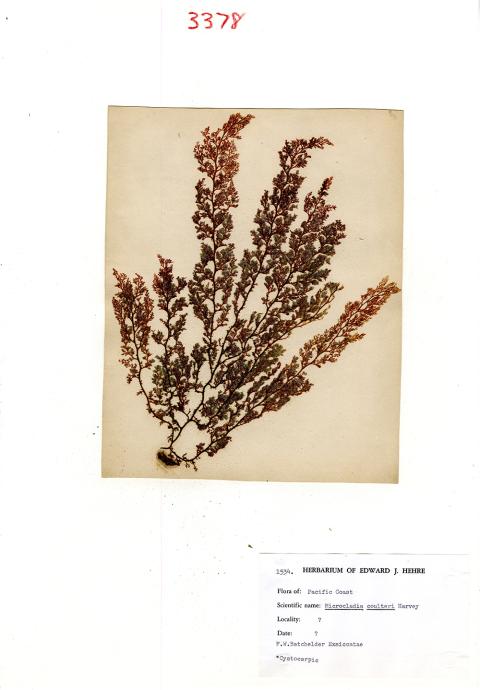

Plymouth State University Herbarium

It was important for the PSU Herbarium to be highlighted as part of this exhibition to emphasize the historical collection, the scientific knowledge, and current research of plant species as important resources to understanding regional eco systems. The work that Professor Diane Jolles and her graduate student Hannah Volmer are doing brings attention to the collaborations and connections between art and science as a means of visual communication for both reflection and for a call to action.

What is an Herbarium?

An herbarium is a curated collection of preserved plant, algae, and fungus specimens used for research. Most specimens are pressed and dried, then mounted on archival paper and stored in large cabinets. The herbarium is organized like a library, where species are organized alphabetically by taxonomic family, genus, and species. Each specimen contains a label with information about who collected it and when, the collection locality, and information about habitat. The information contained on herbarium specimen labels is used to better understand spatiotemporal distribution patterns and how they have changed over time.

The Plymouth State University Herbarium is home to approximately 20,000 specimens representing more than 75% of the New England flora, and it is still growing. Of the 186 regionally rare flowering plants of New England, 68 taxa (37%) are represented by specimens in PSH. Approximately 65% of our specimens are historic, giving us insight into what the flora of New England was like prior to widespread development.

Researchers use herbaria to understand plant diversity. The modern natural historian uses a variety of tools, including genetic techniques, to better understand how species have adapted and changed in response to their environments.

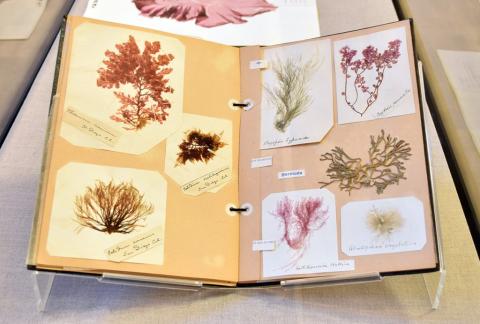

Explore more digitized specimens from the PSU Herbarium’s algae collection.

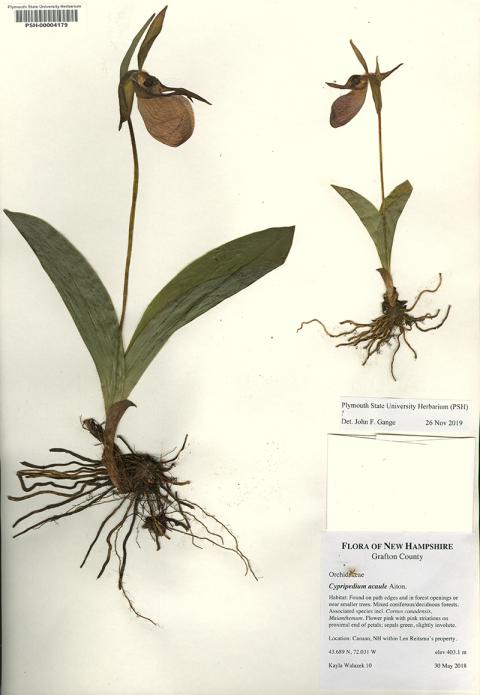

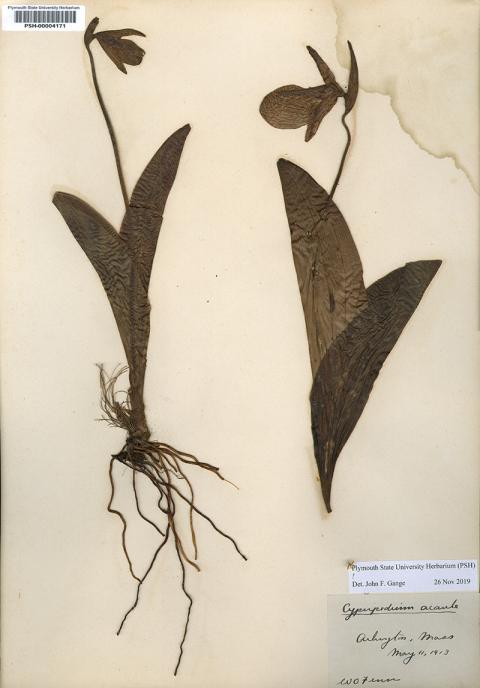

Cypripedium acaule

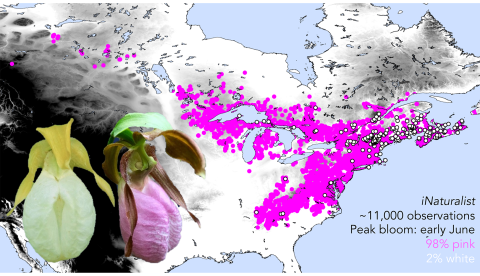

The moccasin flower, aka pink lady’s slipper (Cypripedium acaule) is an iconic forest species in New England and is broadly distributed across the Appalachian Highland and Laurentian Upland physiographic provinces of North America, occurring less abundantly where Eastern Mixed Forest contacts adjacent biomes and where populations are threatened by development.

Several morphotypes of C. acaule exist, including the white-flowered forma albiflora, a taxon described from Mount Desert Island, Maine in 1894. Some people question whether the white form actually exists and whether the color is caused by a somatic mutation (i.e., whether there is a heritable genetic underpinning to this form).

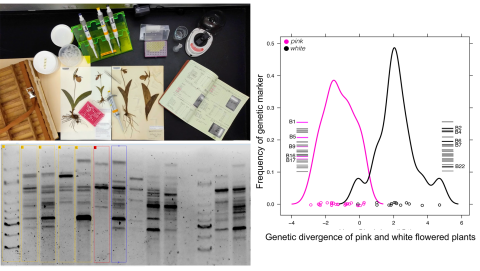

Students at PSU are investigating genetic and environmental aspects of speciation in the moccasin flower. Using GIS (geographic information tools), they extract temperature and precipitation data for thousands of pink and white slipper locations and compare their preferences for different climatic conditions. Climate modelling is a critical first step for understanding lineage diversification and reproductive isolation. Students also use genetic fingerprinting to follow lineage diversification across New England landscapes. Together, these multiple lines of evidence will give us a fuller picture of the natural history of the moccasin flower.

Several morphotypes of C. acaule exist, including forma albiflora, a taxon described from Mount Desert Island, Maine in 1894, and other forms varying primarily in perianth coloration. Still, many have questioned whether the white form actually exists and whether the color is caused by a somatic mutation (i.e., whether there is a heritable genetic underpinning to this form).

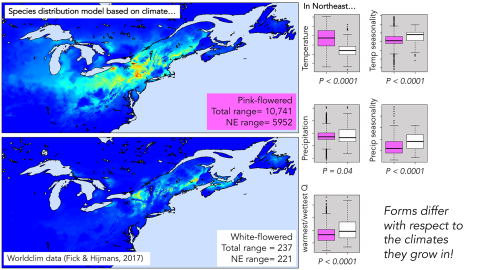

Across the species range there are a number of putative geologic barriers to gene flow, there might be geographic ‘races’ adapted to local climatic conditions. Dr. Jolles’ research lab in the Department of Biological Sciences at Plymouth State University is comparing species distribution models generated from climate data to see whether climatic factors could be involved in reproductive isolation between these two color forms—either as a cause of isolation or a reinforcement of isolation.

Temperature and precipitation data were extracted for 11,000 iNaturalist occurrences of pink and white slippers. After data extraction and climatic model estimation, we conducted basic t-tests to compare mean climate values for pink and white slippers. For the t-tests, the dataset was restricted to a large area of the northeast US and Canada where the white form is most common so that divergence would be less likely obscured by geographic differences. What the Jolles lab observed from these maps is the difference in where one could expect to find each form—red representing a high probability of the form occurring, and blue representing very low probability of finding the form.

T-tests comparing climate for white and pink forms indicate that temperature is a greater predictor of which form will occur in an area than precipitation, with white forms occurring on average in cooler habitats, experiencing greater seasonality throughout the year. Precipitation seasonality was also greater for the white form. Finally, the white form was more common in habitats where precipitation during the warmest and wettest quarters was high. This modelling is a critical first step for looking at lineage diversification to see whether environmental factors can in some way explain reproductive isolation.

Using specimens from herbaria and collections by students, we are investigating whether the different color forms of moccasin flower represent a species complex, a group of closely related, yet genetically distinct species that can interbreed when in close contact. Over geologic time habitats shift and members of a species complex may converge and diverge again many times, producing a pattern called phylogenetic reticulation.

Using specimens from herbaria and collections by students, we are investigating whether the different color forms of moccasin flower represent a species complex, a group of closely related, yet genetically distinct species that can interbreed when in close contact. Over geologic time habitats shift and members of a species complex may converge and diverge again many times, producing a pattern called phylogenetic reticulation.

Marine Algae

The large seaweeds are not plants, but they are extremely diverse, distant relatives that belong to two major taxonomic groups: Rhodophytes (red algae) and Chlorophytes (green algae).

The Plymouth State University Herbarium (PSH) is home to thousands of valuable marine algae specimens representing thousands of species collected from all over the world. The collection was expanded and carefully curated by Dick Fralick (1937-2019), Professor of Botany at PSU for 34 years. Among Fralick’s botanical mentors were notable botanists such as Albion Hodgdon, Arthur Mathieson, and Edward Hehre. Traveling to the coast of New Hampshire to collect and learn about plants and algae was a regular part of Fralick’s courses.

The current Botany Professor at PSU, Diana Jolles, uses the algae collection to teach students about the evolutionary adaptations of plants at sea and on land, with special emphasis on reproduction and photosensitivity.

Solidago

Some of the most iconic landscapes of late summer in New England are open meadows of goldenrod. Often left out of pollinator gardens, many native bees rely exclusively on goldenrod for their nutrition.

Did you know that there are 26 species of Solidago (the goldenrods) in New Hampshire, but this diversity is often overlooked? When you examine these different species all together, the differences in leaf shape and arrangement along the stem, flower size and arrangement, and the architecture of the entire inflorescence (flower head) are quite evident.

Of the approximately 120 species in the genus Solidago worldwide, 25 grow in New England and 23 are represented in the PSU herbarium by multiple specimens collected between 1870 to 1980. Many Solidago are common meadow species, half are associated with wetlands, while others grow in alpine habitats. Two species, Cutler’s goldenrod (S. leiocarpa) and (licorice goldenrod (S. odora) are rare in New Hampshire, and two others are endangered: rough-leaved goldenrod (S. patula) and showy goldenrod (S. speciosa).

Dwarf Cinquefoil Research at Plymouth State University

The White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) has the largest and highest alpine zone in the eastern US, howeverthese areas are relatively small, the natural communities found here are rare, and many alpine plants are imperiled.Dwarf cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana) is one of the rarest flowers in New Hampshire. This species is endemic to the White Mountains, meaning it grows nowhere else in the world.

PSU graduate student, Hannah Vollmer ’21G was awarded a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to research Dwarf cinquefoil in the White Mountains. Hannah and her research on this rare alpine flower were featured on the September 30, 2020 episode of NH Chronicle.

Photos courtesy of Hannah Vollmer and Joe Klementovich.

Dwarf cinquefoil occupies a very niche habitat that has been described as “alpine barrens.”But the term barrens is somewhat of a misnomersince one acre of alpine barrens in particularis a hotbed of dwarf cinquefoil.Thousands of individual plants occupy this small area.

Dwarf cinquefoil habitat isn’t limited to alpine barrens however; a few plants also grow in the cracks of alpine cliffs.

Above treeline on the highest peaks of the White Mountain National Forest, small plants like dwarf cinquefoil are adapted to harsh alpine

conditions such as short growing seasons, high winds, and freezing soils. Though hardy to these extremes, alpine plants are very slow-growing and are easily trampled by hikers who stray off-trail.

Collaborative conservation:

Prior to the conservation movement in the United States, rare plantswereoften collected for study and as curiosities without regard to the sustainability of the species. Dwarf cinquefoil was heavily collected by botanists in the mid 1800’s to early 1900’s. A popular hiking trail also crossed through the main dwarf cinquefoil habitat, leading to further degradation of the population, and in 1980, dwarf cinquefoil was added to the federal Endangered Species List. To restore dwarf cinquefoil to sustainable numbers, a collaborative effort was made

between US Fish & Wildlife Service, the White Mountain National Forest, the Native Plant Trust, and the Appalachian Mountain Club. Plants were nursery-grown and transplanted in its natural habitat to augment the existing population, trails were relocated to avoid its habitat, and a hiker education program was established. By 2002, dwarf cinquefoil had grown back to sustainable levels and became the first plant species to be removed from the federal Endangered Species List. However, this iconic flower is still designated as a Sensitive Species by the WMNF, and as endangered at the state level, and is actively monitored and managed by the WMNF and partners to ensure its continued conservation.

Mature plantsmake the most of their short growing season and flower not long after snowmelt. The seeds develop quickly during early summer and produce many miniscule seedlings, though most do not survive their first winter. It takes 8-13 years for a dwarf cinquefoil plant to reach maturity and flower for the first time. Non–flowering plants less than 1.5 cm in diameter are considered juveniles.

Remarkable reproduction:

This rare species reproduces in a surprising way, though it is not an unusual strategy in the plant kingdom overall. Dwarf cinquefoil is thought to reproduce byapomixis, meaning that seeds are formed without the mixing of genes from two parents, aka sexual reproduction. Apomixis is a form of asexual reproduction and the resulting offspring are genetic clones of the parent plant. This strategy allows a population to be sustainable at lower population levels. However, when all individual plants are genetically identical, there is less ability to adapt or evolve to changing environmental conditions.

While most dwarf cinquefoil plants grow in the stony soil of the alpine barrens, some will take root within small cushions of another alpine plant, diapensia (Diapensialapponica). While larger, spreading mats of diapensia can crowd out dwarf cinquefoil, in this case it seems to be acting like a “nurse log”, providing a protective growing medium for dwarf cinquefoil to take root. Notice the young juveniles below which are likely last year’s successful seedlings.

Small fall foliage:

Dwarf cinquefoil is a perennial species and its leaves die back in the fall. Long taproots keep plants anchored in soil that is prone to frost heaving.

A lone late-season flower blooms in the midst of maturing seed heads.

Sampling leaves for genetic analysis:

While the biology, demographics, and habitat of this species has been well-studied over the last few decades, its genetics have not yet been explored. Leaf tissues are now being analyzed at PSU to assess genetic diversity, or lack thereof, whichwill clarify what its modes of reproduction are and if the subpopulations are distinct from one another. In addition, a small number of seeds were collected to support this genetic study, and to contribute to the New England Plant Conservation Program, led by the Native Plant Trust, which maintains a “seed bank” of the region’s rarest plants as a kind of conservation insurance from the loss of plant populations and genetic diversity in the wild.

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-8.jpg?itok=8gZlMiFX)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-7.jpg?itok=OBZBAspn)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-6.jpg?itok=FP18npZz)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-5.jpg?itok=etWH4TbT)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-4.jpg?itok=IvpUeCge)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-3.jpg?itok=GoB0Mbuk)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-2.jpg?itok=askgu_TI)

![Endangered Invasive Undiscovered [Species] exhibit installation view](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/Endangered-exhibit-view-1.jpg?itok=Nl8-WY8Q)