Drawn to the White Mountains

Ever since the first explorers saw the distant northern mountain peaks as they sailed off the coast of New England, people have been drawn to the White Mountains.

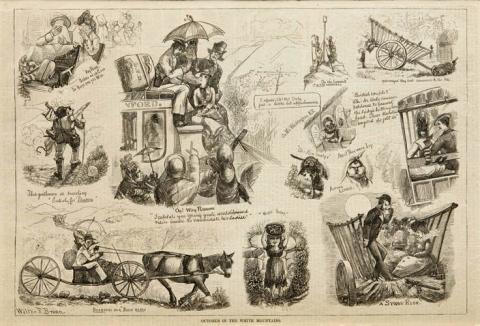

In the nineteenth century, increasing numbers of people escaped urban noise and crowds to explore the sublime beauty of the mountains. There they found a microcosm of the United States, tamed and welcoming locations surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. First seen as a mecca for the elite, changes in travel and accommodations after 1850 opened the White Mountains to the average tourist. Americans’ perceptions of time and space changed and their perceptions of the mountains changed with them.

Philip Carrigain (1772-1842) devoted his working life to developing an accurate map of New Hampshire. Printed in Philadelphia, the map was engraved on six overlapping plates. The six separate pieces were later assembled in Concord to create a single map. (The reproduction Carrigain map on display at the Museum of the White Mountains was also printed in six separate pieces.)

Franconia Notch is known for its curious rock formations such as the Old Man of the Mountain, the Flume, and the Basin. The Old Man was “discovered” during an 1805 survey for a proposed state turnpike through the notch. Articles published between 1826 and 1828 let the world know of these geologic wonders, enticing early travelers to the White Mountains.

“The Great Stone Face, then, was a work of Nature in her mood of majestic playfulness, formed on the perpendicular side of a mountain by some immense rocks, which had been thrown together in such a position as, when viewed at a proper distance, precisely to resemble the features of the human countenance.”

– Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1850

In an October 9, 1828 journal entry, artist Thomas Cole wrote, “Through the pass called Franconia Notch there is a good road on which a small coach passes on its way to Plymouth. After taking a hearty breakfast and securing a little bread and cheese in case of necessity I sallied forth expecting the coach… to overtake me in the Notch.” With the many streams flowing through the Notch and the deep quiet of the region, Cole wrote that he “was often deceived by the sound of falling streams for among these mountains the sound of falling streams is always heard either whispering in the distance or thundering in the foreground.”

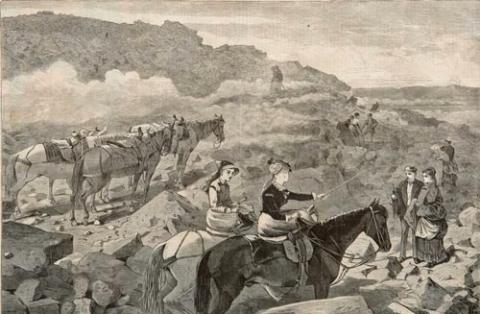

The first visitors to the White Mountains tended to come from three groups: those with wealth and time enough for the slow course through the mountains, those who came to do scientific research, and those who came on business. If travelers walked, they could average 14 to 18 miles per day; with horses, travelers could double the mileage. If they traveled with luggage and needed a coach, their movement could be slower than a walk.

In 1835, Stephen and Joseph Gibbs opened the Lafayette House, the first fashionable hotel in Franconia Notch to provide service to the pleasure traveler. When it first opened, the Lafayette House was so popular that guests often slept on the floor of the parlor when the rooms were full. It was the first of many hotels in the Notch.

Roads reached the mountains, and visitors arrived by coach, wagon or foot. Concord coaches provided the most comfortable ride available: leather suspension straps absorbed many jolts of the road. Even so, the ride could be crowded and uncomfortable. The ride could also be quite slow: the driver had to change horses every 10 to 12 miles and the coach could only maintain a pace of five miles an hour. In the mountains, the pace could be even slower.

The railroad first reached the White Mountains in 1851. The Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad Company built the White Mountain Station House, or Alpine House, at its stop in Gorham. While commercial interest to connect Portland, Maine with Montreal drove the desire for a rail line, the route was chosen in part because of tourist potential. Within a few years, additional railheads encircled the mountains.

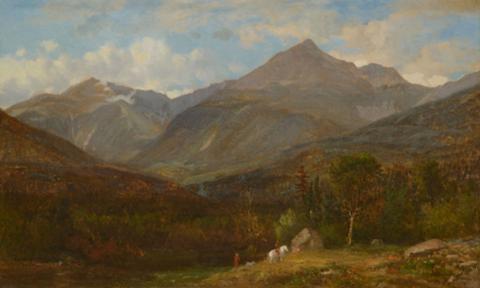

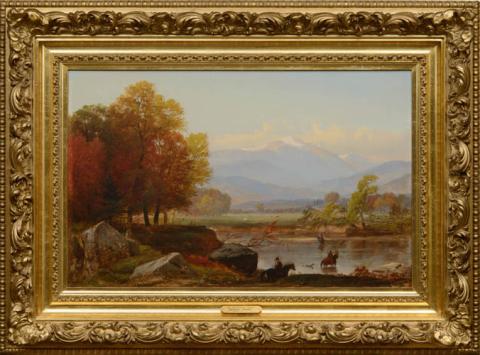

Originally, the Northern Presidentials were depicted with dramatic Alp-like peaks. When artists arrived, they sketched the increasingly tamed and accessible mountains, attracting more tourists. The railroad also opened the timber-rich region to logging.

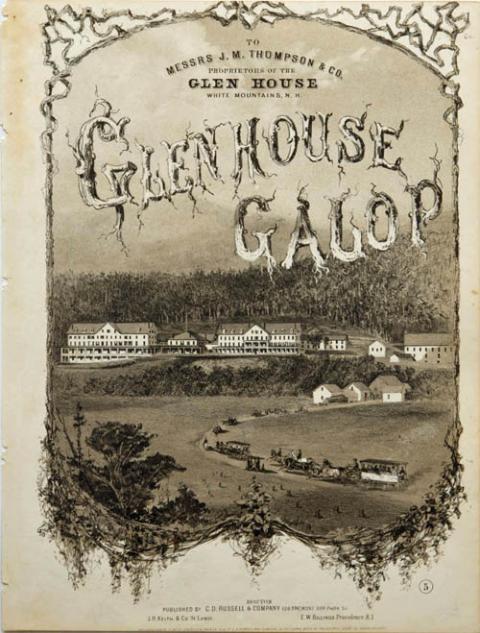

The railway’s instant popularity proved to be both a blessing and a curse. More than a hundred people a day could arrive in Gorham, easily overwhelming the town with people seeking rooms. The Glen House, south of Gorham, profited from the increased number of guests. Accommodations across the region expanded and gained amenities, ushering in the era of the Grand Hotels.

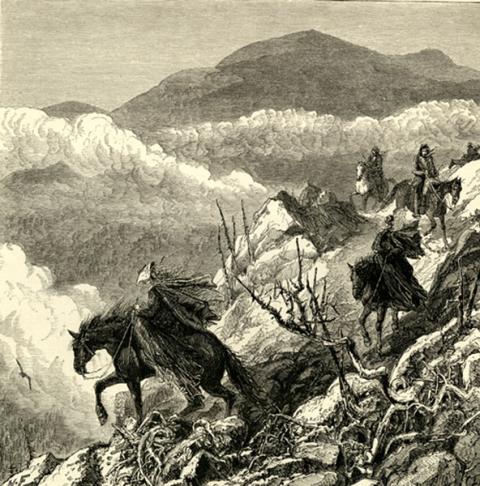

The climb to the top of Mount Washington was the challenge many visitors set for themselves. Hiking, or tramping, became fashionable in the 1820s. Mount Washington has the oldest continuously used trail, built by Ethan Allen Crawford in 1819. Many more were to follow.

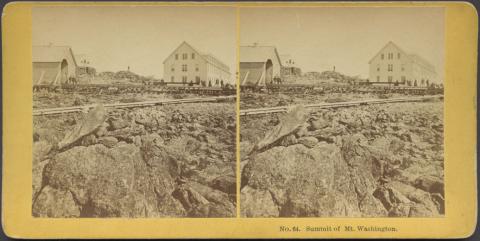

J.S. Hall and L.M. Rosebrook opened the Summit House in July 1852. It was a strong building with small dormitory-style boarding facilities, a larger dining hall for day guests, and walls four-feet thick to withstand the fierce Mr. Washington winds. The next year, Samuel Spaulding built the Tip-Top House with improved dining and kitchen facilities, and walls six-feet thick. The rival facilities offered similar accommodations, including beds filled with moss, separated from the kitchen facilities with heavy cotton drapes.

A toll road, which averaged four hours by coach, was completed from the Glen House to the summit of Mount Washington in 1861. First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln and her son Robert took the Carriage Road to the Tip-Top House on August 6, 1863. They liked the trip so much they repeated it the next day.

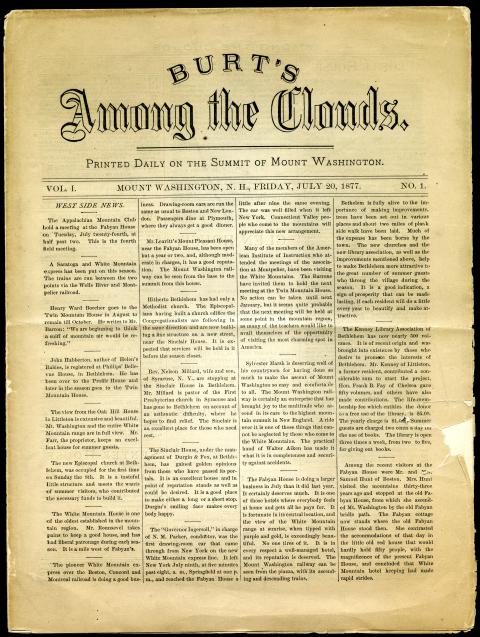

The newspaper Among the Clouds was published at the summit of Mount Washington from 1877 to 1917, except for a short suspension between 1908 and 1909 after a major fire on the summit.

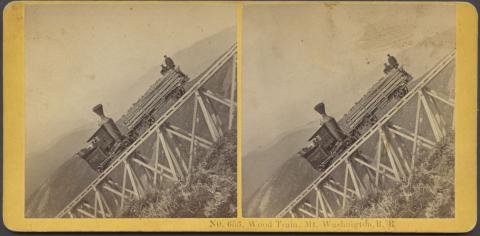

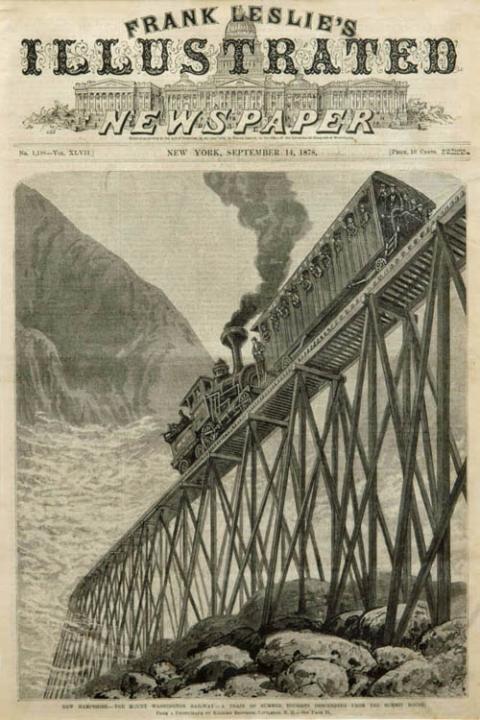

Scientists and inventors were also captivated by the mountains. Starting in the 1830s, botanist Edward Tuckerman spent years studying lichen. Astronomer George Bond published the first topographical map of the White Mountains in 1853. Confounding the experts, Sylvester Marsh developed a cog railway for Mount Washington. When it was completed in 1869, travelers could reach the summit in just an hour and a half.

In 1825, the Willey family moved to Crawford Notch to farm and host overnight travelers. The following summer, a severe storm struck the area. The family, anticipating a destructive rock slide, fled the house for safety but the house remained undisturbed while the Willey family perished. Drawn by the macabre disaster, the number of leisure travelers grew, the ultimate irony for the Willeys.

The Notch was a well-traveled commercial route, especially in the winter. As Nathaniel Hawthorne noted, the road through Crawford Notch was “a great artery through which the lifeblood of internal commerce is continually throbbing between Maine, on one side, and the Green Mountains and the shores of the St. Lawrence, on the other.” Some early travelers stayed with the Crawfords and were so impressed with the area that they hired them as mountain guides.

The Crawfords’ hospitality made them famous. Dr. Samuel Bemis made some of the first daguerreotypes in America, capturing images of the Crawfords’ inns around 1840. Cyrus Eastman and his partners purchased the Crawford House and, in 1859, built a new hotel with added amenities: gas lights, a post office, bowling alleys, gardens, and more. In the late 1870s, Shapleigh painted a nostalgic scene of the Notch House as it would have looked from the Crawford House porch had it not burned in 1859.

The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a wide variety of accommodations opened the White Mountains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures of modern life.

Tourists took home White Mountain art, guidebooks, sheet music, china, and maps that reminded them of their time in the mountains. After the Civil War, the middle class began to holiday in the mountains, away from their lives in the cities. They generally followed a set path and stayed in smaller hotels and boarding houses. With easy access, rapid travel, and comfortable accommodations, civilization had tamed the wilderness.

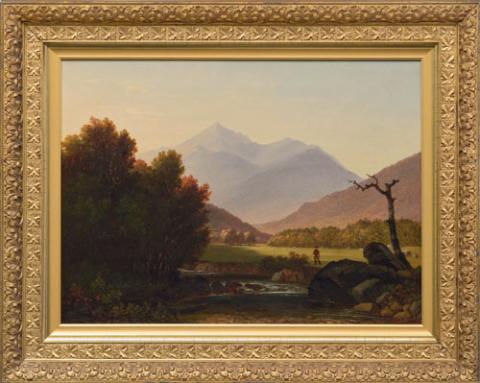

The charismatic artist Benjamin Champney arrived in the White Mountains in 1850, amazed by what he found in Saco Valley. In 1853, he settled in North Conway, where he welcomed clients and artists to his home. As he wrote in his memoire, Sixty Years’ Memories of Art and Artists: “Thus every year brought fresh visitors to North Conway as the news of its attractions spread, until in 1853 and 1854 the meadows and the banks of the Saco were dotted all about with white umbrellas [shielding artists from the summer sun] in great numbers.”

College student F.W. Sanborn left Marblehead, Massachusetts at 6:30 a.m. on a July morning in 1874 and arrived in Lisbon, New Hampshire at 5 p.m. “Our ride of 175 miles was without unpleasantness. There were no disagreeable people on the cars: there were no noisy babies.” His journal includes nothing about the world outside his window. Instead, he was interested in the relaxation and distractions vacation could bring.

Samuel Thompson’s Tavern became a haven for artists beginning in 1850 when Benjamin Champney, John Kensett, and John Casilear discovered the area. Champney noted that by 1852 “there was quite a little knot of artists at Thompson’s and we nearly filled the dining room in the old house.” Thompson made sure that the artists who received special rates signed their paintings identifying the place as “North Conway.” It was good advertising for the artists, the town, and vacationers.

Guidebooks served a variety of purposes for tourists. The Reverend Thomas Starr King‘s 1859 book sought “to direct attention to the noble landscapes that lie along the routes.” Samuel Eastman’s 1858 book described routes through the mountains and included a map. Moses F. Sweetser’s 1876 guidebook gave vivid descriptions of the mountains.

Franklin Leavitt began producing maps of the White Mountains for tourists in 1852. While the maps were “cartographically ludicrous,” when viewed as souvenirs for tourists, they make sense. Large and detailed, the maps conveyed the appeal of the mountains to the city dwellers when travelers brought them home for display. Winter nights studying Leavitt’s maps inspired more people to visit the mountains.